Some thoughts on ‘that speech’, for which I’ve given up my lunch hour:

Cameron set the scene by acknowledging the EU’s greatest achievement: peace in Europe. OK, he slightly undercuts the message by giving NATO a name-check in equal terms, but I suspect that was shoe-horned in there to keep the Liam Foxes happy.

This is actually a good start. What a pity then that he goes on to argue that, its objective achieved, the purpose of the EU now needs to change. Now, Cameron argues, “the main, over-riding purpose of the European Union is different: not to win peace, but to secure prosperity.”

No. No, Mr Cameron, no. No no no. What a thing to say on the day after Germany and France celebrated 50 years of the Elysée Treaty! We have an EU because we know what happens when the countries of Europe do not cooperate. We have an EU because it gives us peace. This cannot be taken for granted. Peace leads to prosperity, but this is emphatically not its over-riding purpose. There is no zero-sum game here; it’s not either peace or prosperity. See this text which I ghost-wrote for Jose Manuel Barroso a few years ago.

So when Cameron says that the EU is not an end in itself, but a means to an end, he fundamentally misunderstands – or perhaps deliberately misrepresents – the philosophy behind the Treaty and the true meaning of the EU to its citizens: the EU is, by its very essence, the negation of war. It represents peace. Its complex, opaque machinery delivers peace each and every day, by bringing together the people who run our society, at all levels, and giving them the habit and the expectation of working together in the common good.

Cameron claims to speaks for his entire country when he says: “we come to the European Union with a frame of mind that is more practical than emotional.” He doesn’t speak for me. I don’t see it as a badge of pride that emotions are left at the door. I do get emotional about government, about politics, about the way in which my society, my civilisation, is run. If think you should get emotional about such things. Be practical too. Again: no need to choose one or the other. You can be both.

So. The Prime Minister sets out his store as a practical man with advice on how to make Europe better. He is not, he insists, driven in any way by emotion (having spent the first few minutes of his speech making emotive points about the British national character, British sovereignty, and the British role in World War II). Defensively, Cameron hedges his advice with a number of strawman arguments:

There are always voices saying “don’t ask the difficult questions.”

Whose are these voices, Dave?

The biggest danger to the European Union comes not from those who advocate change, but from those who denounce new thinking as heresy.

Who are these small ‘c’ conservatives who denounce new thinking as heresy, Dave?

(An aside: bookmark this quote, substituting “Britain” for “the European Union” if you like – it’s as useful an argument against Conservative philosophy as you’re likely to find…)

Let’s welcome that diversity, instead of trying to snuff it out.

Who is trying to snuff out diversity in the EU, Dave? Unless you mean governments which clamp down on minorities, restrict migration, and seek to impose restrictive, traditionalist syllabuses on schools…

The European Treaty commits the Member States to “lay the foundations of an ever closer union among the peoples of Europe”.

This has been consistently interpreted as applying not to the peoples but rather to the states and institutions compounded by a European Court of Justice that has consistently supported greater centralisation.

We understand and respect the right of others to maintain their commitment to this goal. But for Britain – and perhaps for others – it is not the objective.

Is he reneging on the Treaty objective of an ever closer union among the peoples of Europe? Or suggesting that this can be achieved by his recipe of dismantling the institutions of the EU? Either way: I object.

Dave’s big fix for the EU comes in five parts: competitiveness; flexibility; repatriation of powers; democratic accountability; and fairness.

I’m not going to go into a lengthy, point-by-point, take-down of Cameron’s arguments, but do let me point out a few fallacies:

Competitiveness means a level playing field; so does fairness. You do not create, or maintain, a competitive, fair Single Market by repatriating powers on a ‘flexible’ basis. Cherry-picking which rules to follow may be attractive to free riders but it is not the way to make the European economy more competitive.

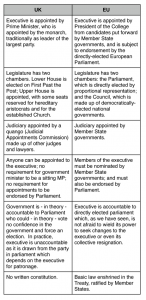

Democratic accountability? Yes please. The quickest, surest, easiest way of achieving this tomorrow would be to loosen the Council’s stranglehold on EU affairs, reversing the path to intergovernmentalism which we have been assiduously hoeing since Maastricht. You want a democratic EU? Then the last thing you do is adopt the Cameron version of “flexibility” by repatriating powers. On the contrary: we need a return to a communautaire European Union. This has the added advantage of being good for competitiveness, and being fairer.

It will be a relationship with the Single Market at its heart.

No it won’t, Dave, not if you’ve opted out of social, environmental, employment, consumer safety legislation. They are as much a part of the Single Market as whole vehicle type approval regulations.

To end with, channelling Herman van Rompuy for a moment, a haiku:

Cameron’s Europe:

“For us, a means to an end”

Now the end is near.